SYNERGIES EUROPÉENNES - Novembre 1989

La "Révolution Conservatrice" en Allemagne (1918-1932)

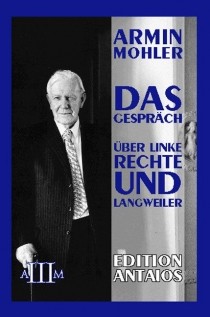

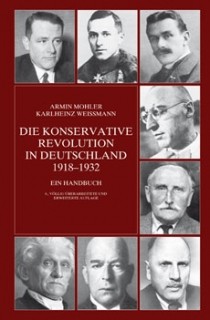

A propos de la réédition tant attendue du célèbre manuel d'Armin Mohler

par Robert STEUCKERS

L'ouvrage d'Armin Mohler sur la "Konservative Revolution" (KR) a été si souvent cité, qu'il est de-venu, dans l'espace linguistique francophone, chez ceux qui cultivent une sorte d'adhésion affective aux idées vitalistes allemandes déri-vées de Nietzsche, une sorte de mythe, de ré-férence mythique très mal connue mais souvent évoquée. Cette année, une réédition a enfin vu le jour, flanquée d'un volume complémen-taire où sont consignés les commentaires de l'auteur sur l'état actuel de la recherche, sur les nou-veaux ou-vrages d'approfondissement et surtout sur les re-cherches de Sternhell (1).

Comment se présente-t-il, finalement, cet ou-vrage de base, ce manuel si fondamental? Il se compose d'abord d'un texte d'initiation, com-mençant à la page 3 de l'ouvrage et s'achevant à la page 169; ensuite d'une bibliographie ex-haustive, recensant tous les ouvrages des au-teurs cités et tous les ouvrages pa-noramiques sur la KR: elle débute à la page 173 pour se ter-miner à la page 483. Suivent alors les annexes, avec la liste des abréviations utilisées pour les lieux d'édition et les maisons d'édition, puis les registres des personnes, des périodiques et des organisations.

Un ouvrage destiné à la recherche

L'ouvrage est donc de prime abord destiné à la re-cherche. Mais comme la thématique englobe des idées, des leitmotive, des affirmations poli-tiques qui ont enthousiasmé de larges strates de l'intelligentsia alle-mande voire une partie des masses, il est évident qu'aujourd'hui encore elle enregistrera des retentis-sements divers en de-hors des cénacles académiques. A Bruxelles, à Genève, à Paris ou à Québec, il n'y a pas que des professeurs qui lisent Ernst Jünger ou Tho-mas Mann... La recension qui suit s'adressera dès lors essentiellement à ce public extra-aca-démique et se con-centrera sur la première partie de l'ouvrage, le texte d'initiation, avec ses défini-tions de concepts, sa clas-sification des diverses strates du phénomène que fut la KR. Mohler, dans ces chapitres d'une densité inouïe, définit très méticuleusement des mouvements politico-idéologiques aussi marginaux que fascinants: les "trots-kystes du national-socialisme", la "Deutsche Be-wegung" (DB), le national-bolché-visme, le "Troi-sième Front" (Dritte Front, en abrégé DF), les Völkischen, les Jungkonser-vativen, les nationaux-révolutionnaires, les Bündischen, etc. ainsi que des concepts comme Weltanschauung, nihilisme, Umschlag, "Grand Midi", réalisme héroïque, etc.

"Konservative Revolution" et national-socialisme

Le premier souci de Mohler, c'est de distinguer la KR du national-socialisme. Pour la tradition antifasciste, souvent imprégnée des démon-strations du marxisme vulgaire, le national-so-cialisme est la continuation politique de la KR. De fait, le national-socialisme a affirmé pour-suivre dans les faits ce que la KR (ou la "Deutsche Bewegung") avait esquissé en esprit. Mais nonobstant cette revendication nationale-socialiste, on est bien obligé de constater, avec Mohler, que la KR d'avant 1933 recelait bien d'autres possibles. Le national-socialisme a constitué un grand mouvement de masse, impres-sionnant dans ses dimensions et affublé de toutes les lourdeurs propres aux appareils de ce type. Face à lui, foisonnaient des petits cercles où l'esprit s'épanouissait indépendamment des vicis-situdes politiques du temps. Ces cénacles d'intel-lec-tuels n'eurent que peu d'influence sur les masses. Le grand parti, en revanche, écrit Mohler, "gardait les masses sous son égide par le biais des liens orga-ni-sationnels et d'une doctrine adaptée à la moyenne et limitée à des slogans; il n'offrait aux têtes supérieures que peu d'espace et seulement dans la mesure où elles voulaient bien participer au travail d'enré-gimentement des masses et limitaient l'exercice de leurs facultés intellectuelles à un quelconque petit domaine ésotérique" (p.4).

Peu d'intellectuels se satisferont de ce rôle de "garde-chiourme de luxe" et préfèreront rester dans cette cha-leur du nid qu'offraient leurs petits cénacles élitaires, où, pensaient-ils, l'"idée vraie" était conservée intacte, tandis que les partis de masse la caricaturaient et la tra-his-saient. Ce réflexe déclencha une cascade de rup-tures, de sécessions, d'excommunications, de conju-ra-tions avec des éléments exclus du parti, si bien que plus aucune équation entre la NSDAP et la KR ne peut honnêtement être posée. Bon nombre de figures de la KR de-vinrent ainsi les "trotskystes du national-so-cialisme", les hérétiques de la "Deutsche Be-wegung", qui seront poursuivis par le régime ou opteront pour l'"émigration intérieure" ou s'insinueront dans cer-taines instances de l'Etat car le degré de la mise au pas totalitaire fut nettement moindre en Allemagne qu'en Union Soviétique. Des représentants éminents de la KR, comme Hans Grimm, Oswald Spengler et Ernst Jünger purent compter sur l'appui de la Reichswehr, des cercles diplomatiques "vieux-conservateurs" ou de cénacles liés à l'industrie. Ne choisissent l'émi-gration que les figures de proue des groupes sociaux-révolutionnaires (Ot-to Strasser, Paetel, Ebeling) ou certains natio-naux-socialistes dissidents comme Rausch-ning. La plupart restent toutefois en Alle-magne, en es-pérant que surviendra une "seconde ré-volution" entièrement conforme à l'"Idée". D'autres se taisent définitivement (Blüher, Hielscher), se ré-fugient dans des préoccupations totalement a-politi-ques ou dans la poésie (Winnig) ou se tournent vers la phi-losophie religieuse (Esch-mann). Très rares seront ceux qui passeront carrément au national-socialisme comme Bäum-ler, spécialiste de Bachofen.

La thèse qui cherche à prouver la "culpabilité an-ticipative" de la KR ne tient pas. En effet, les idées de la KR se retrouvent, sous des formes chaque fois spé-cifiquement nationales, dans tous les pays d'Eu-rope depuis la moitié du XIXième siècle. Si l'on re-trouve des traces de ces idées dans le national-so-cia-lisme allemand, celui-ci, comme nous venons de le voir, n'est qu'une manifestation très partielle et in-com-plète de la KR, et n'a été qu'une tentative parmi des dizaines d'autres possibles. Raisonner en termes de causalité (diabolique) constitue donc, expli-que Moh-ler, un raccourci trop facile, occultant par exemple le fait patent que les conjurés du 20 juillet 1944 ou que Schulze-Boysen, agent so-viétique pendu en 1942, avaient été influencés par les idées de la KR.

L'origine du terme "Konservative Revolution"

Pour éviter toutes les confusions et les amalgames, Mohler pose au préalable quelques définitions: celle de la KR proprement dite, celle de la "Deutsche Be-wegung", celle de la "Weltanschauung" en tant que véhicule pédago-gique des idées nouvelles. Les termes "konser-vativ" et "revolutionär" apparaissent accolés l'un à l'autre pour la première fois dans le journal berlinois Die Volksstimme du 24 mai 1848: le po-lémiste qui les unissait était mani-festement mu par l'intention de persifler, de se gausser de ceux qui agitaient les émotions du public en affirmant tout et le contraire de tout (le conservatisme et la révolution), l'esprit troublé par les excès de bière blanche. En 1851, le couple de vocables réapparait —cette fois dans un sens non polémique— dans un ouvrage sur la Russie attribué à Theobald Buddeus. En 1875, Youri Sa-marine donne pour titre "Re-volyoutsionnyi konser-vatizm" à une plaquette qu'il a rédigée avec F. Dmi-triev. Par la suite, Dostoïevski l'utilisera à son tour. En 1900, Charles Maurras l'emploie dans son Enquête sur la Monarchie. En 1921, Thomas Mann l'utilise dans un article sur la Russie. En Allemagne, le terme "Konservative Revolution" acquiert une vaste no-to-riété quand Hugo von Hoffmannsthal le prononce dans l'un de ses célèbres discours (Das Schriftum als geistiger Raum der Nation — La littérature comme espace spirituel de la nation; 1927). Von Hoff-manns-thal désigne un processus de maturation intellectuel caractérisé par la recherche de "liens", prenant le relais de la recherche de "liberté", et par la recherche de "totalité", d'"unité" pour échapper aux divi-sions et aux discordes, produits de l'ère libérale.

Chez Hoffmannsthal, le concept n'a pas encore d'im-plication politique directe. Mais dans les quelques ti-mi-des essais de politisation de ce concept, dans le con-texte de la République de Weimar agonisante, on per-çoit très nettement une volonté de mettre à l'avant-plan les ca-ractéristiques immuables de l'âme humaine, en réaction contre les idées de 1789 qui pariaient sur la perfectibilité infinie de l'homme. Mais tous les cou-rants qui s'opposèrent jadis à la Révolution Française ne débouchent pas sur la KR. Bon nombre d'entre eux restent simplement partisans de la Restauration, de la Réaction, sont des conservateurs de la vieille école (Altkonservativen).

"Konservative Revolution" et "Deutsche Bewegung"

Donc si la KR est un refus des idées de 1789, elle n'est pas nostalgie de l'Ancien Régime: elle opte con-fusément, parfois plus clairement, pour une "troisième voie", où seraient absentes l'anarchie, l'absence de valeurs, la fascination du laissez-faire propres au li-béralisme, l'immoralité fondamentale du règne de l'ar-gent, les rigidités de l'Ancien Régime et des abso-lutismes royaux, les platitudes des socialismes et com-munismes d'essence marxiste, les stratégies d'a-ra-sement du passé ("Du passé, faisons table rase..."). A l'aube du XIXième siècle, entre la Révolution et la Restauration, surgit, sur la scène philoso-phique euro-péenne, l'idéalisme allemand, réponse au rationalisme français et à l'empirisme anglais. Parallèlement à cet idéalisme, le roman-tisme secoue les âmes. Sur le ter-rain, comme dans le Tiers-Monde aujourd'hui, les Al-le-mands, exaltés par Fichte, Arndt, Jahn, etc., pren-nent les armes contre Napoléon, incarnation d'un co-lo-nialisme "occidental". Ce mélange de guerre de li-bé-ration, de révolution sociale et de retour sur soi-même, sur sa propre identité, constitue une sorte de préfiguration de la KR, laquelle serait alors le stade atteint par la "Deutsche Bewegung" dans les années 20.

Pour en résumer l'esprit, explique Mohler, il faut mé-diter une citation tirée du célébrissime roman de D.H. Lawrence, The plumed Serpent (= Le serpent à plu-mes, 1926). Ecoutons-la: "Lorsque les Mexicains apprennent le nom de Quetzalcoatl, ils ne devraient le prononcer qu'avec la langue de leur propre sang. Je voudrais que le monde teutonique se mette à repenser dans l'esprit de Thor, de Wotan et d'Yggdrasil, le frêne qui est axe du monde, que les pays druidiques comprennent que leur mystère se trouve dans le gui, qu'ils sont eux-mêmes le Tuatha de Danaan, qu'ils sont ce peuple toujours en vie même s'il a un jour sombré. Les peuples méditerranéens devraient se réapproprier leur Hermès et Tunis son Astharoth; en Perse, c'est Mithra qui devrait ressusciter, en Inde Brahma et en Chine le plus vieux des dragons".

Avec Herder, les Allemands ont élaboré et conservé une philosophie qui cherche, elle aussi, à renouer avec les essences intimes des peuples; de cette philosophie sont issus les nationalismes germaniques et slaves. Dans le sens où elle recherche les essences (tout en les préservant et en en conservant les virtualités) et veut les poser comme socles d'un avenir radicalement neuf (donc révolutionnaire), la KR se rapproche du na-tionalisme allemand mais acquiert simultanément une valeur universelle (et non universaliste) dans le sens où la diversité des modes de vie, des pensées, des âmes et des corps, est un fait universel, tandis que l'univer-salisme, sous quelque forme qu'il se présente, cherche à biffer cette prolixité au profit d'un schéma équarisseur qui n'a rien d'universel mais tout de l'ab-straction.

La notion de "Weltanschauung"

La KR, à défaut d'être une philosophie rigoureuse de type universitaire, est un éventail de Weltan-schau-ungen. Tandis que la philoso-phie fait partie intégrante de la pensée du vieil Occident, la Weltanschauung apparaît au moment où l'édifice occidental s'effondre. Jadis, les catégories étaient bien contingentées: la pensée, les sentiments, la volonté ne se mêlaient pas en des flux désordonnés comme aujour-d'hui. Mais désormais, dans notre "interrègne", qui succède à l'ef-fondrement du christianisme, les Weltan-schau-ungen mêlent pensées, senti-ments et volontés au sein d'une tension perpé-tuelle et dynamisante. La pensée, soutenue par des Weltanschauungen, détient désor-mais un caractère instrumental: on sollicite une mul-titu-de de disciplines pour illustrer des idées déjà pré-alablement conçues, acceptées, choisies. Et ces idées servent à atteindre des objectifs dans la réalité elle-même. La nature particulière (et non plus universelle) de toute pensée nous révèle un monde bigarré, un chaos dynamique, en mutation perpétuelle. Selon Mohler, les Weltanschauungen ne sont plus véhicu-lées par de purs philosophes ou de purs poètes mais par des êtres hybrides, mi-penseurs, mi-poètes, qui savent conjuguer habilement —et avec une cer-taine cohérence— concepts et images. Les gestes de l'existence concrète jouent un rôle primordial chez ces penseurs-poètes: songeons à T.E. Lawrence (d'Ara-bie), Malraux et Ernst Jünger. Leurs existences enga-gées leur ont fait touché du doigt les nerfs de la vie, leur a communiqué une expérience des choses bien plus vive et forte que celle des philosophes et des théologiens, même les plus audacieux.

L'opposition concept/image

Les mots et les concepts sont donc insuffisants pour cerner la réalité dans toute sa multiplicité. La parole du poète, l'image, leur sont de loin supérieures. L'ère nouvelle se reflète dès lors davantage dans les travaux des "intellectuels anti-intellectuels", de ceux qui peu-vent, avec génie, manier les images. Un passage du journal de Gerhard Nebel, daté du 19 novembre 1943, illustre parfaitement les positions de Mohler quand il sou-ligne l'importance de la Weltanschauung par rap-port à la philosophie classique et surtout quand il en-tonne son plaidoyer pour l'intensité de l'existence contre la grisaille des théories, plaidoyer qu'il a ré-sumé dans le concept de "nominalisme" et qui a eu le reten-tissement que l'on sait dans la maturation intel-lectuelle de la "Nouvelle Droite" française (3).

Ecoutons donc les paroles de Gerhard Nebel: "Le rap-port entre les deux instruments méta-physiques de l'homme, le concept et l'image, livre à ceux qui veu-lent s'exercer à la com-paraison une matière inépui-sable. On peut dire, ainsi, que le concept est impro-ductif, dans la mesure où il ne fait qu'ordonner ce qui nous tombe sous le sens, ce que nous avons déjà dé-couvert, ce qui est à notre disposition, tandis que l'image génère de la réalité spirituelle et ramène à la surface des éléments jusqu'alors cachés de l'Etre. Le concept opère prudemment des distinctions et des re-groupements dans le cadre strict des faits sûrs; l'image saisit les choses, avec l'impétuosité de l'aventurier et son absence de tout scrupule, et les lance vers le large et l'infini. Le concept vit de peurs; l'image vit du faste triomphant de la découverte. Le concept doit tuer sa proie (s'il n'a pas déjà ramassé rien qu'un cadavre), tandis que l'image fait apparaître une vie toute pétil-lante. Le concept, en tant que concept, exclut tout mys-tère; l'image est une unité paradoxale de contraires, qui nous éclaire tout en honorant l'obscur. Le concept est vieillot; l'image est toujours fraîche et jeune. Le concept est la victime du temps et vieillit vite; l'image est toujours au-delà du temps. Le concept est subor-donné au progrès, tout comme les sciences, elles aussi, appartiennent à la caté-gorie du progrès, tandis que l'image relève de l'instant. Le concept est écono-mie; l'image est gaspillage. Le concept est ce qu'il est; l'image est toujours davantage que ce qu'elle semble être. Le concept sollicite le cerveau mais l'image solli-cite le cœur. Le concept ne meut qu'une périphérie de l'existen-ce; l'image, elle, agit sur l'ensemble de l'existence, sur son noyau. Le concept est fini; l'image, infinie. Le concept simplifie; l'image honore la diversité. Le concept prend parti; l'image s'abstient de juger. Le concept est gé-néral; l'image est avant tout individuelle et, même là où l'on peut faire de l'image une image générale et où l'on peut lui subordonner des phénomènes, cette action de subordonnance rap-pelle des chasses passionnantes; l'ennui que suscite l'inclusion, l'enfermement de faits de monde dans des concepts, reste étranger à l'image...".

Les idées véhiculées par les Weltanschauungen s'incarnent dans le réel arbitrairement, de façon impré-visible, discontinue. En effet, ces idées ne sont plus des idées pures, elles n'ont plus une place fixe et immuable dans une quelconque empyrée, au-delà de la réalité. Elles sont bien au contraire imbriquées, pri-sonnières des aléas du réel, soumises à ses mutations, aux conflits qui forment sa trame. Etudier l'impact des Weltan-schauungen, dont celles de la KR, c'est poser une topographie de courants souterrains, qui ne sau-tent pas directement aux yeux de l'obser-vateur.

Une exigence de la KR: dépasser le wilhelminisme

Quand Arthur Moeller van den Bruck parle d'un "Troisième Reich" en 1923 (4), il ne songe évidem-ment pas à l'Etat hitlérien, dont rien ne laisse alors prévoir l'avènement, mais d'un système politique qui succéderait au IIième Reich bismarcko-wilhelminien et où les oppo-sitions entre le socialisme et le nationa-lisme, en-tre la gauche et la droite seraient sublimées en une synthèse nouvelle. De plus, cette idée d'un "troisième" Empire, ajoute Mohler, renoue avec toute une spéculation philosophique christiano-européenne très ancienne, qui parlait d'un troisième règne comme du règne de l'esprit (saint). Dès le IIième siècle, les montanistes, secte chrétienne, évoquent l'avènement d'un règne de l'esprit saint, successeur des règnes de Dieu le Père (ancien testament) et de Dieu le Fils (nouveau testament et incarnation), qui serait la syn-thèse parfaite des contraires. Dans le cadre de l'histoire allemande, on repère une longue aspiration à la syn-thèse, à la conciliation de l'inconciliable: par exemple, entre les Habs-bourg et les Hohenzollern. Après la Grande Guer-re, après la réconciliation nationale dans le sang et les tranchées, Moeller van den Bruck est l'un de ces hommes qui espèrent une synthèse entre la gauche et la droite par le truchement d'un "troisième parti". Evidemment, les hitlé-riens, en fondant leur "troisième Reich", prétendront transposer dans le réel toutes ses vieilles aspirations pour les asseoir définiti-ve-ment dans l'histoire. La KR et/ou la "Deutsche Be-wegung" se scinde alors en deux groupes: ceux qui estiment que le IIIième Reich de Hitler est une falsifi-cation et entrent en dissidence, et ceux qui pensent que c'est une première étape vers le but ultime et acceptent le fait accompli.

Sous le IIième Reich historique, existait une "opposition de droite", mécontente du caractère libé-ral/darwiniste de la révolution industrielle allemande, du rôle de l'industrie et du grand capital, de l'étroitesse d'esprit bourgeoise, du façadisme pompeux, avec ses stucs et son tape-à-l'oeil. Le "conservatisme" officiel de l'époque n'est plus qu'un décor, que poses mata-mores-ques, tandis que l'économie devient le destin. Ce bourgeoisisme à colifichets militaires suscite des réactions. Les unes sont réformistes; les autres exigent une rupture radicale. Parmi les réfor-mistes, il faut compter le mouvement chrétien-social du Pasteur Adolf Stoecker, luttant pour un "Empire social", pour une "voie caritative" vers la justice sociale. Les élé-ments les plus dynami-ques du mouvement finiront par adhérer à la sociale-démocratie. Quant au "Mouvement Pan-Ger-maniste" (Alldeutscher Verband), il sombre-ra dans un impérialisme utopique, sur fond de roman-tisme niais et de cliquetis de sabre. Les autres mouve-ments restent périphériques: les mouvements "artistiques" de masse, les mar-xistes qui veulent une voie nationale, les pre-miers "Völkischen", etc.

A l'ombre de Nietzsche...

Face à ces réformateurs qui ne débouchent sur rien ou disparaissent parce que récupérés, se trouvent d'abord quelques isolés. Des isolés qui mûrissent et agissent à l'ombre de Nietzsche, ce penseur qui ne peut être classé parmi les prota-gonistes de la "Deutsche Bewe-gung" ni parmi les précurseurs de la KR, bien que, sans lui et sans son œuvre, cette dernière n'aurait pas été telle qu'elle fut. Mais comme les isolés qu'a-limente la pensée de Nietzsche sont nombreux, très différents les uns des autres, il s'en trouve quelques-uns qui amorcent véritablement le processus de maturation de la KR. Mohler en cite deux, très importants: Paul de Lagarde et Julius Langbehn. L'orientaliste Paul de La-garde voulait fonder une religion allemande, appelée à remplacer et à renforcer le message des christia-nismes protestants et catholiques en pariant sur la veine mys-tique, notamment celle de Meister Eckhart le Rhénan et de Ruusbroeck le Bra-bançon (5). Julius Langbehn est surtout l'homme d'un livre, Rembrandt als Erzieher (1890; = Rembrandt éducateur) (6). A partir de la person-nalité de Rembrandt, Langbehn chante la mysti-que profonde du Nord-Ouest européen et sug-gère une synthèse entre la rudesse froide mais vertueuse du Nord et l'enthousiasme du Sud.

Mouvement völkisch et mouvement de jeunesse

En marge de ses deux isolés, qui connurent un succès retentissant, deux courants sociaux contri-buent à briser les hypocrisies et le matérialisme de l'ère wilhelmi-nienne: le mouvement völkisch et le mouvement de jeunesse (Jugendbewe-gung). Par völkisch, nous ex-plique Mohler, l'on entend les groupes animés par une philosophie qui pose l'homme comme essentiellement dépen-dant de ses origines, que celles-ci proviennent d'une matière informelle, la race, ou du travail de l'histoire (le peuple ou la tribu étant, dans cette op-tique, forgé par une histoire longue et com-mune). Proches de l'idéologie völkische sont les doctrines qui posent l'homme comme déterminé par un "paysage spirituel" ou par la langue qu'il parle. Dans les années 1880, le mouvement völkisch se constitue en un front du refus assez catégorique: il est surtout antisémite et remplace l'ancien antisémitisme confessionnel par un antisémitisme "raciste" et déterministe, lequel prétend que le Juif reste juif en dépit de ses options person-nelles réelles ou affectées. Le mouvement völkisch se divise en deux tendan-ces, l'une aristocratique, dirigée par Max Lieber-mann von Sonnenberg, qui cherche à rapprocher certaines catégories du peuple de l'aristocratie conservatrice; l'autre est radicale, démo-cratique et issue de la base. C'est en Hesse que cette pre-mière radicalité völkische se hissera au niveau d'un parti de masse, sous l'impulsion d'Otto Böckel, le "roi des paysans hessois", qui renoue avec les souvenirs de la grande guerre des paysans du XVIième siècle et rêve d'un soulève-ment généralisé contre les grands capitalistes (dont les Juifs) et les Junker, alliés objectifs des premiers.

Le mouvement de jeunesse est une révolte des jeunes contre les pères, contre l'artificialité du wilhelminisme, contre les conventions qui étouf-fent les cœurs. Créé par Karl Fischer en 1896, devenu le "Wandervogel" (= "oiseau migra-teur") en 1901, le mouvement connait des dé-buts anarchisants et romantiques, avec des éco-liers et lycéens, coiffés de bérets fantaisistes et la gui-tare en bandoulière, qui partent en randon-née, pour quitter les villes et découvrir la beauté des paysages (7). A partir de 1910-1913, le mou-vement de jeunesse acquerra une forme plus stricte et plus disciplinée: la principale organisation porteuse de ce renouveau fut la Frei-deutsche Jugend (8).

Le choc de 1914

Quand éclate la guerre de 1914, les peuples croient à une ultime épreuve purgative qui pulvérisera les bar-rières de partis, de classes, de confessions, etc. et conduira à la "totalité" espé-rée. Thomas Mann, dans les premières semaines de la guerre, parle de "purification", de grand nettoyage par le vide qui ba-laiera le bric-à-brac wilhelminien. Peu importaient la victoire, les motifs, les intérêts: seule comptait la guerre comme hygiène, aux yeux des peuples lassés par les artifices bourgeois. Mais les enthousiasmes du début s'enliseront, après la bataille de la Marne, dans la guerre des tranchées et dans l'implacable choc mé-canique des matériels. "Toute finesse a été broyée, piétinée", écrit Ernst Jünger. Le XIXième siècle périt dans ce maelstrom de fer et de feu, les façades rhéto-riques s'écroulent pulvérisées, les contingente-ments proprets perdent tout crédit et deviennent ridicules.

De cette tourmente, surgit, discrète, une nouvelle "totalité", une "totalité" spartiate, une "totalité" de souffrances, avec des alternances de joies et de morts. Une chose apparaît certai-ne, écrit encore Ernst Jünger, c'est "que la vie, dans son noyau le plus intime, est indestructi-ble". Un philosophe ami d'Ernst Jünger, Hugo Fischer, décrit cet avènement de la totalité nou-velle, dans un essai de guerre paru dans la revue "nationale-bolchévique" Widerstand (Janvier 1934; "Der deutsche Infanterist von 1917"): "Le culte des grands mots n'a plus de raison d'être aujourd'hui... La guerre mondiale a été le dai-mon qui a fracassé et pulvérisé le pathétisme. La guerre n'a plus de com-mencement ni de fin, le fantassin gris se trouve quelque part au mi-lieu des masses de terre boueuse qui s'étendent à perte de vue; il est dans son trou sale, prêt à bondir; il est un rien au sein d'une monotonie grise et désolée, qui a toujours été telle et sera toujours telle mais, en même temps, il est le point focal d'une nou-velle souveraineté. Là-bas, quelque part, il y avait ja-dis de beaux systèmes, scrupuleusement construits, des systèmes de tran--chées et d'abris; ces systèmes ne l'intéres-sent plus; il reste là, debout, ou s'accroupit, à moitié mort de soif, quelque part dans la campagne libre et ouverte; l'opposition entre la vie et la mort est repoussée à la lisière de ses souvenirs. Il n'est ni un individu ni une com-munauté, il est une particule d'une force élé-mentaire, planant au-dessus des champs rava-gés. Les concepts ont été bouleversés dans sa tête. Les vieux concepts. Les écailles lui tombent des yeux. Dans le brouillard infini, que scrutent les yeux de son esprit, l'aube semble se lever et il commence, sans sa-voir ce qu'il fait, à penser dans les catégories du siècle prochain. Les ca-nons balayent cette mer de saletés et de pourriture, qui avait été le domaine de son exis-tence, et les entonnoirs qu'ont creusés les obus sont sa demeure (...) Il a survécu à toutes les formes de guerre; le voilà, incorruptible et immortel, et il ne sait plus ce qui est beau, ce qui est laid. Son regard pénètre les choses avec la tranquillité d'un jet de flamme. Avec ou sans mérite, il est resté, a survécu (...) L'"intériorité" s'est projetée vers l'extérieur, s'est transformée de fond en comble, et cette extériorité est devenue totale; intériorité et extériorité fusion-nent; (...) On ne peut plus distinguer quand l'extériorité s'arrête et quand l'homme com-mence; celui-ci ne laisse plus rien derrière lui qui pourrait être réservée à une sphère privée".

La défaite de 1918: une nécessité

En novembre 1918, l'Etat allemand wilhelminien a cessé d'exister: la vieille droite parle du "coup de cou-teau dans le dos", œuvre des gau-ches qui ont trahi une armée sur le point de vaincre. Dans cette perspective, la défaite n'est qu'un hasard. Mais pour les tenants de la KR, la défaite est une nécessité et il convient main-tenant de déchiffrer le sens de cette défaite. Franz Schauwecker, figure de la mouvance na-tio-nale-révolu-tionnaire, écrit: "Nous devions perdre la guerre pour gagner la Nation". Car une victoire de l'Allemagne wilhelminienne aurait été une défaite de l'"Allemagne secrète". L'écrivain Edwin Erich Dwin-ger, de père nord-allemand et de mère russe, engagé à 17 ans dans un régiment de dragons, prisonnier en Si-bérie, combattant enrôlé de force dans les armées rouge et blanche, revenu en Allemagne en 1920, met cette idée dans la bouche d'un pope russe, personnage de sa trilogie romanesque consacrée à la Russie (9): "Vous l'avez perdue la grande Guerre, c'est sûr... Mais qui sait, cela vaut peut-être mieux ainsi? Car si vous l'aviez gagnée, Dieu vous aurait quitté... L'orgueil et l'oppres-sion [du wilhelminisme, ndt] se seraient multi-pliées par cent; une jouissance vide de sens aurait tué toute étincelle divine en vous... Un pourrissement rapide vous aurait frappé; vous n'auriez pas connu de véritable ascension... Si vous aviez ga-gné, vous seriez en fin de course... Mais maintenant vous êtes face à une nouvelle aurore...".

Après la guerre vient la République de Weimar, mal aimée parce qu'elle perpétue, sous des ori-peaux répu-blicains, le style de vie bourgeois, celui du parvenu. Cette situation est inaccepta-ble pour les guerriers reve-nus des tranchées: dans cette république bourgeoise, qui a troqué les uniformes chamarrés et les casques à pointe contre les fracs des notaires et des banquiers, ils "bivouaquent dans les appartements bourgeois, ne pouvant plus renoncer à la simplicité virile de la vie militaire", comme le disait l'un d'eux. Ils seront les recrues idéales des partis extrémistes, communiste ou national-socialiste. La Républi-que de Weimar se dé-ploiera en trois phases: une phase tumultueuse, s'étendant de novembre 1918, avec la proclamation de la République, à la fin de 1923, quand les Français quittent la Ruhr et que le putsch Hitler/Ludendorff est maté à Munich; une phase de calme, qui durera jus-qu'à la crise de 1929, où la République, sous l'impulsion de Stresemann, jugule l'inflation et où les passions semblent s'apaiser. A partir de la crise, l'édifice répu-blicain vole en éclats et les nationaux-socialistes sortent vainqueurs de l'arène.

Le débourgeoisement total

La République de Weimar a connu des débuts très dif-ficiles: elle a dû mater dix-huit coups de force de la gauche et trois coups de force de la droite, sans compter les manœuvres séparatistes en Rhénanie, fo-mentées par la France. Dans cette tourmente, on en est arrivé à une situation (apparemment) absurde: un gou-vernement en majorité socialiste appelle les ouvriers à la grève générale pour bloquer le putsch d'extrême-droite de Kapp; cette grève générale est l'étincelle qui déclenche l'insurrection communiste de la Ruhr et, pour étrangler celle-ci, le gouvernement ap-pel-le les sympathisants des putschistes de Kapp à la rescousse! La situation était telle que l'esprit public, secoué, pre-nait une cure sévère de dé-bourgeoisement.

Bien sûr, le débourgeoisement total n'affectaient qu'une infime minorité, mais cette minorité était quand même assez nombreuse pour que ses attitudes et son esprit déteignent quelque peu sur l'opinion publique et sur la mentalité générale de l'époque. La guerre avait arraché plusieurs clas-ses d'âge au confort bourgeois, lequel n'exerçait plus le moindre attrait sur elles. Pour ces hommes jeunes, la vie active du guerrier était qua-litativement supérieure à celle du bourgeois et ils haïs-saient l'idée de se morfondre dans des fauteuils mous, les pantoufles aux pieds. C'est pourquoi l'ardeur de la guerre, ils allaient la rechercher et la retrouver dans les "Corps Francs", ceux de l'intérieur et ceux de l'ex-térieur. Ceux de l'intérieur se moulaient dans les structures d'auto-défense locales (Einwohner-wehr) et permettaient, en fin de compte, un retour progressif à la vie civile, assorti quand même d'une promptitude à reprendre l'assaut dans les rangs communistes ou, surtout, na-tionaux-socialistes. Ceux de l'extérieur, qui combattaient les Polonais en Haute-Silésie et avaient arraché l'Annaberg de haute lutte, ou affrontaient les armées bolchéviques dans le Baltikum, regroupaient des soldats perdus, de nouveaux lansquenets, des irré-cupérables pour la vie bourgeoise, des pélérins de l'absolu, des vagabonds spartiates en prise directe avec l'élé-mentaire. Dans leurs âmes sauvages, l'esprit de la KR s'incrustera dans sa plus pure quin-tessence.

Parallèlement aux Corps Francs, d'autres structures d'accueil existaient pour les jeunes et les soldats fa-rouches: les Bünde du mouvement de jeunesse, lequel, avec la guerre, avait perdu toutes ses fantaisies anar-chistes et abandonné toutes ses rêveries philoso-phiques et idéalistes. Ensuite les partis de toutes obé-diences recru-taient ces ensauvagés, ces inquiets, ces cheva-liers de l'élémentaire pour les engager dans leurs formations de combat, leurs services d'ordre. Avant le choc de la guerre, le révolutionnaire typique ne renon-çait par radicalement aux for-mes de l'existence bour-geoise: il contestait simplement le fait que ces formes, assorties de richesses et de positions sociales avanta-geuses, étaient réservées à une petite minorité. L'engage-ment du révolutionnaire d'avant 1914 visait à généraliser ces formes bourgeoises d'existence, à les étendre à l'ensemble de la société, classe ouvrière comprise. Le révolutionnaire de type nou-veau, en re-vanche, ne partage pas cet uto-pisme eudémoniste: il veut éradiquer toute référence à ces valeurs bour-geoises haïes, tout sentiment positif envers elles. Pour le bourgeois frileux, convaincu de détenir la vérité, la formule de toute civilisation, le révolutionnaire nouveau est un "nihiliste", un dangereux mar-ginal, un personnage inquiétant.

Les lansquenets modernes

Mais les partis bourgeois, battus en brèche, incapables de faire face aux aléas qu'étaient les exigences des Al-liés et les dérèglements de l'économie mondiale, la violence de la rue et la famine des classes défavori-sées, ont été obligés de recourir à la force pour se maintenir en selle et de faire appel à ces lansquenets modernes pour encadrer leurs militants. Ces cadres issus des Corps Francs se rendent alors incontour-nables au sein des partis qui les utilisent, mais conservent toujours une certaine distance, en marge du gros des militants.

Ce processus n'est pas seulement vrai pour le national-socialisme, avec ses turbulents SA. Chez les commu-nistes, des bandes de solides bagarreurs adhèrent au Roter Kampfbund. Cer-taines organisations restent in-dépendantes for-mellement, comme le Kampfbund Wi-king du Capitaine Hermann Ehrhardt, le Bund Ober-land du Capitaine Beppo Römer et du Dr. Friedrich Weber, le Wehrwolf de Fritz Kloppe et la Reichs-flagge du Capitaine Adolf Heiß. Le Stahl-helm, orga-nisation paramilitaire d'anciens com-battants, dirigée par Seldte et Duesterberg, est proche des Deutschna-tionalen (DNVP). Le Jungdeutscher Orde (Jungdo) de Mahraun sert de service d'ordre à la Demokratische Partei. Quant aux sociaux-démocrates (SPD), leur or-ganisation paramilitaire s'appelait le Reichs-ban-ner Schwarz-Rot-Gold, dont les chefs étaient Hörsing et Höltermann.

La quasi similitude entre toutes ses formations faisait que l'on passait allègrement de l'une à l'autre, au gré des conflits personnels. Beppo Römer quittera ainsi l'Oberland pour passer à la KPD communiste. Bodo Uhse (10) fera exacte-ment le même itinéraire, mais en passant par la NSDAP et le mouvement révolution-naire pay-san, la Landvolkbewegung. Giesecke passera de la KPD à la NSDAP. Contre les Français dans la Ruhr, les militants communistes sabotent instal-lations et voies ferrées sous la conduite d'of-ficiers prussiens; SA et Roter Kampfbund colla-borent contre le gouver-nement à Berlin en 1930-31.

Dans ce contexte, Mohler souligne surtout l'apparition et la maturation de deux mouve-ments d'idées, le fa-meux "national-bolché-visme" et le "Troisième Front" (Dritte Front). Si l'on analyse de façon dualiste l'affrontement majeur de l'époque, entre nationaux-so-cialistes et communistes, l'on dira que l'idéologie des forces communistes dérive des idées de 1789, tan-dis que celles du national-socialisme de cel-les de 1813, de la Deutsche Bewegung. Il n'em-pêche que, dans une plage d'intersection réduite, des contacts fructueux entre les deux mondes se sont produits. Dans quelques cerveaux perti-nents, un socialisme ra-dical fusionne avec un nationalisme tout aussi radical, afin de sceller l'alliance des deux nations "prolétariennes", l'Allemagne et la Russie, contre l'Occident capitaliste.

Trois vagues de national-bolchévisme

Trois vagues de "national-bolchévisme" se suc-céde-ront. La première date de 1919/1920. Elle est une ré-action directe contre Versailles et atteint son apogée lors de la guerre russo-polonaise de 1920. La section de Hambourg de la KPD, dirigée par Heinrich Lauf-fenberg et Fritz Wolffheim, appelle à la guerre popu-laire et nationale contre l'Occident (11). Rapidement, des contacts sont pris avec des nationalistes de pure eau comme le Comte Ernst zu Reventlow. Quand la cavalerie de Boudienny se rapproche du Corridor de Dantzig, un espoir fou germe: foncer vers l'Ouest avec l'Armée Rouge et réduire à néant le nouvel ordre de Versailles. Weygand, en réorganisant l'armée polo-naise en août 1920, brise l'élan russe et annihile les espoirs allemands. Lauffenberg et Wolffheim sont ex-communiés par le Komintern et leur nouvelle organi-sation, la KAPD (Kommunisti-sche Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands), se mue en une secte insignifiante.

La seconde vague date de 1923, quand l'occupation de la Ruhr et l'inflation obligent une nouvelle fois natio-nalisme et communisme à fusionner. Radek, fonction-naire du Komintern, rend un vibrant hommage à Schlageter, fusillé par les Français. Moeller van den Bruck répond. Un dialogue voit le jour. Dans le jour-nal Die Rote Fahne, on peut lire les lignes suivantes, parfaitement à même de satisfaire et les natio-nalistes et les communistes: "La Nation s'effrite. L'héritage du prolétariat allemand, créé par les peines de générations d'ouvriers est menacé par la botte des militaristes fran-çais et par la faiblesse et la lâcheté de la bourgeoi-sie alle-mande, fébrile à l'idée de récolter ses petits pro-fits. Seule la classe ouvrière peut désormais sauver la Nation". Mais cette seconde vague natio-nale-bol-chéviste n'est restée qu'un symptôme de fièvre: d'un côté comme de l'autre, on s'est contenté de formuler de belles proclamations.

Plus sérieuse sera la troisième vague nationale-bolchéviste, explique Mohler. Elle s'amorce dès 1930. A la crise économique mondiale et à ses effets sociaux, s'ajoute le Plan de réparations de l'Américain Young qui réduit encore les maigres ressources des Alle-mands. Une fois de plus, les questions nationale et so-ciale se mêlent étroite-ment. Gregor Strasser, chef de l'aile gauche de la NSDAP, et Heinz Neumann, tacti-cien commu-niste du rapprochement avec les natio-naux, parlent abondamment de l'aspiration anti-capita-liste du peuple allemand. Des officiers natio-nalistes, aristocratiques voire nationaux-socia-listes, passent à la KPD comme le célèbre Lieutenant Scheringer, Ludwig Renn, le Comte Alexander Stenbock-Fermor, les chefs de la Landvolkbewegung comme Bodo Uhse ou Bruno von Salomon, le Capitaine des Corps Francs Beppo Römer, héros de l'épisode de l'Annaberg. Dans la pratique, la KPD soutient l'initiative du Stahl-helm contre le gouvernement prussien en août 1931; communistes et natio-naux-socialistes organisent de concert la grève des transports en commun berlinois de novem-bre 1932. Toutes ces alliances demeurent ponc-tuel-les et strictement tactiques, donc sans lendemain.

La tendance anti-russe de la NSDAP munichoise (Hitler et Rosenberg) réduit à néant le tandem KPD/NSDAP, particulièrement bien rodé à Berlin. L'URSS signe des pactes de non-agression avec la Pologne (25.1.1932) et avec la France (29.11.1932). Au sein de la KPD, la tendance Thälmann, internatio-naliste et anti-fas-ciste, l'emporte sur la tendance Neu-mann, socia-liste et nationale.

Mais ce national-bolchévisme idéologique et militant, présent dans de larges couches de la population, du moins dans les plus turbulentes, a son pendant dans certains cercles très influents de la diplomatie, regrou-pés autour du "Comte rouge", Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau, et du Baron von Maltzan. La position de Brockdorff-Rantzau était en fait plus nuancée qu'on ne l'a cru. Quoi qu'il en soit, leur optique était de se dé-gager des exigences françaises en jouant la carte russe, exactement dans le même esprit de la politique prussienne russophile de 1813 (les "Accords de Taurog-gen"), tout en voulant reconstituer un équilibre euro-péen à la Bis-marck.

Le "troisième front" (Dritte Front)

Pour distinguer clairement la KR du national-socia-lisme, il faut savoir, explique Mohler, qu'avant la "Nuit des Longs Couteaux" du 30 juin 1934, où Hit-ler élimine quelques adversai-res et concurrents, inté-rieurs et extérieurs, le national-socialisme est une idéologie floue, re-celant virtuellement plusieurs pos-sibles. Ce fut, selon les circonstances, à la fois sa force et sa faiblesse face à un communisme à la doc-trine claire, nette mais trop souvent rigide. Mohler énumère quelques types humains rassemblés sous la bannière hitlérienne: des ouvriers re-belles, des resca-pés de l'aventure des Corps Francs de la Baltique, des boutiquiers en colère qui veulent faire supprimer les magasins à rayons multiples, des entrepreneurs qui veulent la paix sociale et des débouchés extérieurs nouveaux. Sur le plan de la politique étrangère, les options sont également diverses: alliance avec l'Italie fasciste contre le bolchévisme; al-lian-ce de tous les pays germaniques avec mini-misation des rapports avec les peuples du Sud, décrétés "fellahisés"; alliance avec une Russie redevenue plus nationale et débarrassée de ses velléités communistes et internationalistes, afin de forger un pacte indéfectible des "have-nots" con-tre les nations capitalistes. De plus, la NSDAP des premières années du pouvoir, compte dans ses rangs des fédéra-listes bavarois et des centralistes prussiens, des catho-liques et des protestants convaincus, et, enfin, des mi-litants farouchement hostiles à toutes les formes de christianisme.

Cette panade idéologique complexe est le propre des partis de masse et Hitler, pour des raisons pratiques et tactiques, tenait à ce que le flou soit conservé, afin de garder un maximum de militants et d'électeurs. Avant la prise du pou-voir, plusieurs tenants de la KR avaient constaté que cette démagogie contribuerait tôt ou tard à falsifier et à galvauder l'idée précise, tranchée et argu-mentée qu'ils se faisaient de la nation. Pour éviter l'avènement de la falsification nationale-socialiste et/ou communiste, il fallait à leurs yeux créer un "troisième front" (Dritte Front), basé sur une synthèse cohérente et destiné à remplacer le système de Weimar. Entre le drapeau rouge de la KPD et les chemises brunes de la NSDAP, les dissidents optent pour le drapeau noir de la révolte paysanne, hissé par les révoltés du XVIième siècle et par les amis de Claus Heim (12). Le drapeau noir est "le dra-peau de la terre et de la misère, de la nuit allemande et de l'état d'alerte".

Le rôle de Hans Zehrer

L'un des partisans les plus chaleureux de ce "troisième front" fut Hans Zehrer, éditeur de la revue Die Tat d'octobre 1931 à 1933. Dans un article intitulé signifi-cativement Rechts oder Links? (Die Tat, 23. Jg., H.7, Okt. 1931), Zehrer explique que l'anti-libéralisme en Allemagne s'est scindé en deux ailes, une aile droite et une aile gauche. L'aile droite puise dans le réservoir des sentiments nationaux mais fait passer les questions sociales au second plan. L'aile gauche, elle, accorde le primat aux questions sociales et tente de gagner du ter-rain en matière de nationalisme. Le camp des anti-libéraux est donc partagé entre deux pôles: le national et le social. Cette opposition risque à moyen ou long terme d'épuiser les combattants, de lasser les masses et de n'aboutir à rien. En fin de course, les appareils dirigeants des partis communiste et national-socialiste ne défendent pas les intérêts fondamentaux de la po-pulation, mais exclusive-ment leurs propres intérêts. Les bases des deux partis devraient, écrit Zehrer, se détourner de leurs chefs et se regrouper en une "troisième communauté", qui serait la synthèse parfaite des pôles social et national, antagonisés à mau-vais escient.

Derrière Zehrer se profilait l'ombre du Général von Schleicher qui, lui, cherchait à sauver Weimar en atti-rant dans un "troisième front" les groupes socialisants internes à la NSDAP (Gre-gor Strasser), quelques syn-dicalistes sociaux-dé-mocrates, etc. Mais l'assem-bla-ge était trop hétéroclite: KPD et NSDAP ré-sistent à l'entre-prise de fractionnement. Le "troisième front" ne sera qu'un rassemblement de groupes situés "entre deux chaises", sans force motrice dé-cisive.

Robert STEUCKERS.

(La suite de cette recension, rendant compte d'un ouvrage abso-lument capital pour comprendre le mouvement des idées poli-tiques de notre siècle, paraîtra dans nos éditions ultérieures. Nous mettrons l'accent sur les fondements philosophiques de la KR et sur ses principaux groupes).

Armin MOHLER, Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918-1932. Ein Handbuch (Dritte, um einen Ergänzungsband erweiterte Auflage 1989), Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darm-stadt, 1989, I-XXX + 567 S., Ergänzungsband, I-VIII + 131 S., DM 89 (beide zusammen); DM 37 (Ergänzungsband einzeln).

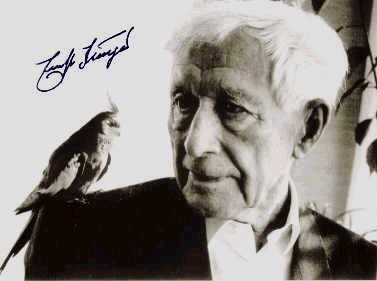

Molti giovani promesse del pensiero anticonformista degli anni ‘70 conservano ancora oggi il nitido ricordo delle visite da “Meister Locchi” presso la sua casa di Saint-Cloud, a Parigi, «casa dove molti giovani francesi, italiani e tedeschi si recavano più in pellegrinaggio che in visita; ma simulando indifferenza, nella speranza che Locchi […] fosse come Zarathustra dell’umore giusto per vaticinare anziché, come disgraziatamente faceva più spesso, parlare del tempo o del suo cane o di attualità irrilevanti»1. Le ragioni di una tale venerazione non possono sfuggire anche a chi l’autore romano lo abbia conosciuto solo tramite i suoi testi. Leggere Locchi, infatti, è un’“esperienza di verità”: aprendo il suo Wagner, Nietzsche e il mito sovrumanista – un «grande libro», «uno dei testi classici dell’ermeneutica wagneriana», come lo definisce Paolo Isotta sul… “Corriere della Sera”!2 – ci si trova di fronte al disvelamento (ἀλήθεια, a-letheia) di un sapere originale ed originario. Disvelamento che non può mai essere totale.

Molti giovani promesse del pensiero anticonformista degli anni ‘70 conservano ancora oggi il nitido ricordo delle visite da “Meister Locchi” presso la sua casa di Saint-Cloud, a Parigi, «casa dove molti giovani francesi, italiani e tedeschi si recavano più in pellegrinaggio che in visita; ma simulando indifferenza, nella speranza che Locchi […] fosse come Zarathustra dell’umore giusto per vaticinare anziché, come disgraziatamente faceva più spesso, parlare del tempo o del suo cane o di attualità irrilevanti»1. Le ragioni di una tale venerazione non possono sfuggire anche a chi l’autore romano lo abbia conosciuto solo tramite i suoi testi. Leggere Locchi, infatti, è un’“esperienza di verità”: aprendo il suo Wagner, Nietzsche e il mito sovrumanista – un «grande libro», «uno dei testi classici dell’ermeneutica wagneriana», come lo definisce Paolo Isotta sul… “Corriere della Sera”!2 – ci si trova di fronte al disvelamento (ἀλήθεια, a-letheia) di un sapere originale ed originario. Disvelamento che non può mai essere totale. Il punto di partenza del pensiero locchiano è il rifiuto di ogni determinismo storico, ovvero l’idea che «la storia – il divenire storico dell’uomo – scaturisca dalla storicità stessa dell’uomo, cioè dalla libertà storica dell’uomo e dall’esercizio sempre rinnovato che di questa libertà storica, di generazione in generazione, fanno personalità umane differenti»4. È il rifiuto della “logica dell’inevitabile”. La storia è sempre aperta e determinabile dalla volontà umana. Due sono, a livello macro-storico, gli esiti possibili, i poli opposti verso cui indirizzare il divenire: la tendenza egualitarista e la tendenza sovrumanista, esemplificate da Nietzsche con i due mitemi del trionfo dell’ultimo uomo e dell’avvento del superuomo (o, se si preferisce, dell’“oltreuomo”, come è stato rinominato da Vattimo nell’intento illusorio di depotenziarne la carica rivoluzionaria). Il filosofo della volontà di potenza afferma la libertà storica dell’uomo tramite l’annuncio della morte di Dio: chi ha acquisito la consapevolezza che “Dio è morto” «non crede più di essere governato da una legge storica che lo trascende e lo conduce, con l’umanità intera, verso un fine – ed una fine – della storia predeterminato ab aeterno o a principio; bensì sa ormai che è l’uomo stesso, in ogni “presente” della storia, a stabilire conflittualmente la legge con cui determinare l’avvenire dell’umanità»5.

Il punto di partenza del pensiero locchiano è il rifiuto di ogni determinismo storico, ovvero l’idea che «la storia – il divenire storico dell’uomo – scaturisca dalla storicità stessa dell’uomo, cioè dalla libertà storica dell’uomo e dall’esercizio sempre rinnovato che di questa libertà storica, di generazione in generazione, fanno personalità umane differenti»4. È il rifiuto della “logica dell’inevitabile”. La storia è sempre aperta e determinabile dalla volontà umana. Due sono, a livello macro-storico, gli esiti possibili, i poli opposti verso cui indirizzare il divenire: la tendenza egualitarista e la tendenza sovrumanista, esemplificate da Nietzsche con i due mitemi del trionfo dell’ultimo uomo e dell’avvento del superuomo (o, se si preferisce, dell’“oltreuomo”, come è stato rinominato da Vattimo nell’intento illusorio di depotenziarne la carica rivoluzionaria). Il filosofo della volontà di potenza afferma la libertà storica dell’uomo tramite l’annuncio della morte di Dio: chi ha acquisito la consapevolezza che “Dio è morto” «non crede più di essere governato da una legge storica che lo trascende e lo conduce, con l’umanità intera, verso un fine – ed una fine – della storia predeterminato ab aeterno o a principio; bensì sa ormai che è l’uomo stesso, in ogni “presente” della storia, a stabilire conflittualmente la legge con cui determinare l’avvenire dell’umanità»5. Il “conflitto epocale” è dato dallo scontro di due tendenze antagoniste. Si è già detto quale siano le tendenze della nostra epoca: egualitarismo e sovrumanismo. Ogni tendenza attraversa tre fasi: quella mitica (in cui sorge una nuova visione del mondo in modo ancora istintuale, come sentimento del mondo non razionalizzato e quindi come unità dei contrari), quella ideologica (in cui la tendenza, affermandosi storicamente, comincia a riflettere su se stessa e quindi si divide in differenti ideologie apparentemente contrapposte tra loro) e quella autocritica o sintetica (in cui la tendenza prende atto della sua divisione ideologica e cerca di ricreare artificialmente la propria unità originaria). E se l’egualitarismo (oggi in fase “sintetica”) è la tendenza storica dominante da duemila anni, la prima espressione “mitica” del sovrumanismo va ricercata nei movimenti fascisti europei.

Il “conflitto epocale” è dato dallo scontro di due tendenze antagoniste. Si è già detto quale siano le tendenze della nostra epoca: egualitarismo e sovrumanismo. Ogni tendenza attraversa tre fasi: quella mitica (in cui sorge una nuova visione del mondo in modo ancora istintuale, come sentimento del mondo non razionalizzato e quindi come unità dei contrari), quella ideologica (in cui la tendenza, affermandosi storicamente, comincia a riflettere su se stessa e quindi si divide in differenti ideologie apparentemente contrapposte tra loro) e quella autocritica o sintetica (in cui la tendenza prende atto della sua divisione ideologica e cerca di ricreare artificialmente la propria unità originaria). E se l’egualitarismo (oggi in fase “sintetica”) è la tendenza storica dominante da duemila anni, la prima espressione “mitica” del sovrumanismo va ricercata nei movimenti fascisti europei. Ma il primo tentativo di agire concretamente nella storia da parte della tendenza sovrumanista, come sappiamo, è sfociato nella sconfitta militare europea del 1945. Una sconfitta che ha posto il vecchio continente tra le fauci della tenaglia costruita a Yalta. In quel periodo, è bene ricordarlo, troppi eredi del mondo uscito perdente dal secondo conflitto mondiale pensarono di rinverdire la loro militanza sostenendo uno dei due bracci della tenaglia a scapito dell’altro, vagheggiando di un Occidente “bianco” che altro non poteva essere se non la “terra della sera” (Abend-land) in cui veder tramontare ogni speranza di rinascita europea. Scelsero, quei “fascisti” vecchi o nuovi, la tattica del “male minore”. Che, notoriamente, non è altro che la tattica dell’“utile idiota” vista… dall’utile idiota.

Ma il primo tentativo di agire concretamente nella storia da parte della tendenza sovrumanista, come sappiamo, è sfociato nella sconfitta militare europea del 1945. Una sconfitta che ha posto il vecchio continente tra le fauci della tenaglia costruita a Yalta. In quel periodo, è bene ricordarlo, troppi eredi del mondo uscito perdente dal secondo conflitto mondiale pensarono di rinverdire la loro militanza sostenendo uno dei due bracci della tenaglia a scapito dell’altro, vagheggiando di un Occidente “bianco” che altro non poteva essere se non la “terra della sera” (Abend-land) in cui veder tramontare ogni speranza di rinascita europea. Scelsero, quei “fascisti” vecchi o nuovi, la tattica del “male minore”. Che, notoriamente, non è altro che la tattica dell’“utile idiota” vista… dall’utile idiota.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

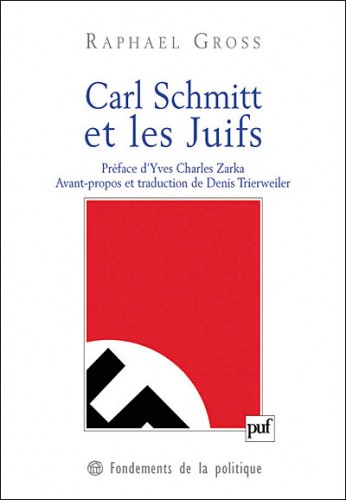

Le livre :

Le livre :

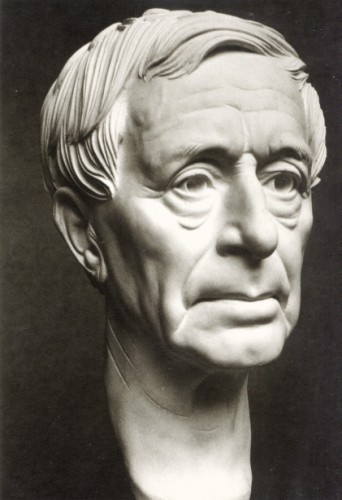

sich zu bezeichnen angewohnt hat. Insbesondere sein sowohl wissenschaftlichen Ansprüchen wie allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung gerecht werdendes Buch „Preußen. Geschichte eines Staates“ (1) ist als geschichtliche Einführung bis heute unübertroffen. Eine von Schoeps veranstaltete Preußen-Anthologie „Das war Preußen. Zeugnisse der Jahrhunderte“ wurde im übrigen von Julius Evola ins Italienische übersetzt. (2)

sich zu bezeichnen angewohnt hat. Insbesondere sein sowohl wissenschaftlichen Ansprüchen wie allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung gerecht werdendes Buch „Preußen. Geschichte eines Staates“ (1) ist als geschichtliche Einführung bis heute unübertroffen. Eine von Schoeps veranstaltete Preußen-Anthologie „Das war Preußen. Zeugnisse der Jahrhunderte“ wurde im übrigen von Julius Evola ins Italienische übersetzt. (2)

In seinem Buch „Gottheit und Menschheit. Die großen Religionsstifter und ihre Lehren“ (Stuttgart: Steingrüben 1950) nimmt Schoeps auch zum Islam Stellung, es hat aber den Anschein, dies geschähe mehr der Vollständigkeit halber als von Interesse oder Kompetenz her. Schoeps reiht einige der Platitüden der Orientalistik über den unoriginellen, allzumenschlichen usw. Propheten des Islam aneinander und charakterisiert den Islam als in seinem Prädestitationsdenken und seiner Schicksalsgläubigkeit „calvinistisch“, was genauso sinnvoll ist, wie das Christentum – unter Ausblendung all seiner anderen Strömungen – als calvinistisch zu bezeichnen. Tatsächlich schreibt Schoeps auch von der entgegengesetzten „pantheistischen“ Strömung, die Einseitigkeit durch eine zweite ergänzend. Denn in Wirklichkeit ist Ibn Arabi als wichtigster Vertreter des esoterischen Islam genausowenig pantheistisch wie Shankara, Meister Eckart oder Lao-Tse, deren grundsätzliche Identität mit seiner „Mystik“ oder vielmehr Gnosis aufgezeigt werden kann. Auch das beklagte „allzumenschliche“ also anscheinend unethische Verhalten des Propheten muß hinterfragt werden, denn es beruht auf einigen späten Hadithen. Träte uns Muhammad als fehlerlose Idealgestalt entgegen, wären die Orientalisten sofort bei der Stelle, um den geschichtlichen Wahrheitsgehalt dieser Stellen in Zweifel zu ziehen. Tatsächlich sind diese Berichte über Fehler und unmoralisches Verhalten aber Hadithen – vorwiegend aus der „Hadithfabrik“ von

In seinem Buch „Gottheit und Menschheit. Die großen Religionsstifter und ihre Lehren“ (Stuttgart: Steingrüben 1950) nimmt Schoeps auch zum Islam Stellung, es hat aber den Anschein, dies geschähe mehr der Vollständigkeit halber als von Interesse oder Kompetenz her. Schoeps reiht einige der Platitüden der Orientalistik über den unoriginellen, allzumenschlichen usw. Propheten des Islam aneinander und charakterisiert den Islam als in seinem Prädestitationsdenken und seiner Schicksalsgläubigkeit „calvinistisch“, was genauso sinnvoll ist, wie das Christentum – unter Ausblendung all seiner anderen Strömungen – als calvinistisch zu bezeichnen. Tatsächlich schreibt Schoeps auch von der entgegengesetzten „pantheistischen“ Strömung, die Einseitigkeit durch eine zweite ergänzend. Denn in Wirklichkeit ist Ibn Arabi als wichtigster Vertreter des esoterischen Islam genausowenig pantheistisch wie Shankara, Meister Eckart oder Lao-Tse, deren grundsätzliche Identität mit seiner „Mystik“ oder vielmehr Gnosis aufgezeigt werden kann. Auch das beklagte „allzumenschliche“ also anscheinend unethische Verhalten des Propheten muß hinterfragt werden, denn es beruht auf einigen späten Hadithen. Träte uns Muhammad als fehlerlose Idealgestalt entgegen, wären die Orientalisten sofort bei der Stelle, um den geschichtlichen Wahrheitsgehalt dieser Stellen in Zweifel zu ziehen. Tatsächlich sind diese Berichte über Fehler und unmoralisches Verhalten aber Hadithen – vorwiegend aus der „Hadithfabrik“ von

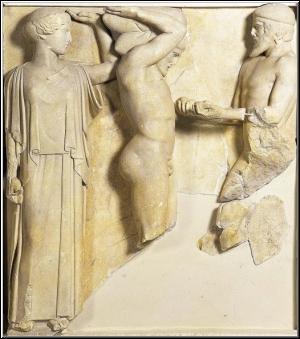

Each High Culture has as a distinguishing feature a "prime symbol." The Egyptian symbol, for example, was the "Way" or "Path," which can be seen in the ancient Egyptians' preoccupation -- in religion, art, and architecture (the pyramids) -- with the sequential passages of the soul. The prime symbol of the Classical culture was the "point-present" concern, that is, the fascination with the nearby, the small, the "space" of immediate and logical visibility: note here Euclidean geometry, the two-dimensional style of Classical painting and relief-sculpture (you will never see a vanishing point in the background, that is, where there is a background at all), and especially: the lack of facial expression of Grecian busts and statues, signifying nothing behind or beyond the outward. [Image: Atlas Bringing Heracles the Golden Apples in the presence of Athena, a metope illustrating Heracles' Eleventh Labor, with Athena helping Heracles hold up the sky. From the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, c. 460 BC.]

Each High Culture has as a distinguishing feature a "prime symbol." The Egyptian symbol, for example, was the "Way" or "Path," which can be seen in the ancient Egyptians' preoccupation -- in religion, art, and architecture (the pyramids) -- with the sequential passages of the soul. The prime symbol of the Classical culture was the "point-present" concern, that is, the fascination with the nearby, the small, the "space" of immediate and logical visibility: note here Euclidean geometry, the two-dimensional style of Classical painting and relief-sculpture (you will never see a vanishing point in the background, that is, where there is a background at all), and especially: the lack of facial expression of Grecian busts and statues, signifying nothing behind or beyond the outward. [Image: Atlas Bringing Heracles the Golden Apples in the presence of Athena, a metope illustrating Heracles' Eleventh Labor, with Athena helping Heracles hold up the sky. From the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, c. 460 BC.]